Memes and Internet Dreams: Indigenous Art in Online Space

Tatiana Povoroznyuk

ARTH376: Arts of The Northwest Coast: The North

April 7, 2020

The story of Indigenous art on the Northwest coast can be understood as characterised by European representative formats clashing with Indigenous world-view and ideology. Only recently has the larger art world ‘accepted’ Indigenous visual forms into the Western definition of art, and only recently have cultural institutions begun to focus on Indigenous voices as fundamental to the interpretation of their own culture’s artwork[1]. These institutions are eager to innovate in this regard, but their histories of upholding colonial ideologies can not be easily written off. With the proliferation of the internet—a potentially boundless space for self-representation—several scholars have contemplated the possibilities of Indigeneity and cyberspace. Loretta Todd’s speculated on the future of digital space in 1996, asking if Indigenous “narratives, histories, languages, and knowledge can find meaning in cyberspace”, understanding the internet as emerging out of a Western need to transcend the earthly plane[2]. Ahasiw Maskegon-Iskew was a dedicated advocate for Indigenous presence on the Internet, understanding indigenous world-view as intrinsically networked, and advocates for the use of the Internet to combat colonialism on a global level[3]. As recent decades have solidified the Internet as the defining feature of our time, Todd’s concerns have had time to develop. Indeed, many of the same pre-Internet hierarchies of power have persisted; with a handful of corporations controlling most communication, and the presence of art online commonly occurring through channels of museums funded through the same governments and corporate donors. However, this narrative is continually being challenged by Northwest coast artists, and Indigenous world-view is actively being carved out in online space. I bring Wuulhu’s (Bracken Hanuse Corlett) recent work Emergency Indigenous Meme Machine in conversation with these scholars, understanding the work as an assertion of Indigenous resistance within online space. The internet is not a boundless and utopic space for Indigenous Northwest Coast art, but as it continues to evolve Indigenous artists are constantly working to make space for themselves within cyberspace, challenging the colonial constructs inherent in traditional museums.

The museum has undergone a conceptual overhaul in recent decades, but the medium itself maintains certain colonial implications when considering the display of Indigenous visual material. As distilled by Anna Laura Jones in a review of the topic, the most basic critique of the museum format is that “museums, particularly museums of art, continue to treat this material as exemplifying primitive qualities.[4]” Tracing the same history, Ames delineates four antiquated (and yet active) museological methodologies which have worked to reduce and misrepresent Northwest coast cultures since the historical advent of museums—the “cabinet of curiosities”, the natural history approach, contextualized exhibits, and formalist art exhibitions[5]. The issue with these approaches within ethnographic museums is a consistent refusal to include Indigenous sources of knowledge in their own representations, continually favouring the institutionally-approved academic perspective. Art museums exist at the opposite end of this spectrum, with the presentation of works through formalist aesthetics, fitting Indigenous cultural practices within Western paradigms of post-modernist aesthetics. This ignorance effectively replicates colonial structures of knowledge, favoring Western perspectives above all in the presentation of Indigenous work. Ames was highly critical of these practices within his career as MOA’s director, calling on an “insiders point of view”, and “partnership” between institutions and indigenous peoples[6]. However, a redemptive narrative for museums like MOA is questioned by figures such as Hal Foster, who understands that “no anthropological remorse, aesthetic elevation, redemptive exhibition can correct or compensate this loss because they [cultural institutions] are all implicated in it[7]”. Jones summarizes current thought on the issue as “Challenging the conventional authority of curators and institutions and sharing real power over representations” being the “wave of the future[8]” for the discipline. However, in an age of instantaneous transmission of images and ideas over the internet, is it possible that this representative power need not be shared?

The potentialities embodied by the Internet have interested Indigenous scholars as a medium which can challenge these structures of power and create space which exists in line with Indigeneity rather than at odds with it. Loretta Todd approaches the subject with caution, instigating a complex line of inquiry which centers on the Cree concept of clean land; “Can our narratives, histories, languages, and knowledge find meaning in cyberspace? And above all, can cyberspace help keep Ka-Kanata a clean land?”[9]. Todd understands Cyberspace as unfinished, as existing between potentialities of upholding colonial power relations or existing as a tool to rupture them. Maskegon-Iskenew acknowledges the shortcomings of cyberspace at length, acknowledging the globalizing dominance of contemporary culture permeating through this space. Ultimately, however, Maskgegon-Iskenew builds a complex understanding of the conflation of Indigeneity and the Internet, firstly by asserting Indigenous culture as characteristically networked, citing an ancient and intrinsic capability to adapt; "The ancient process of successfully adapting to their worlds' shifting threats and opportunities—innovating the application of best practices to suit complex and shifting flows—from a position of equality and autonomy within them[10]". From this understanding, Maskegon-Iskew describes the animasphere, an

“interconnected antispeciocentric constellation of the cosmosphere (astronomic and electromagnetic realms), the geosphere, the atmosphere, the hydrosphere, and the biosphere…each with diverse and overlapping delegates shaping worldviews among Indigenous cultures that form the foundation of their languages and identities” [11].

Indigenous art, particularly within the network is imagined as being driven by a need to reclaim and re-envision this animaspehere and combat globalized capitalism, reversing the “drive towards mass suicidal ecologic destruction”[12]. Todd’s essay is cautious and adamantly aware of the spiritual implications of cyberspace as a method of escapism for the body and soul, but she ends her work with an inkling of hope; “A place where people can find their own dream. Not just fantasies of abandon, but dreams of humanity and of ways to keep the land clean.[13]”

Wuulhu’s Emergency Indigenous Meme Machine engages with these notions of networked Indigeneity, of both the potential to revive the animasphere to combat globalized capitalism and the ways in which Northwest coast Indigenous culture adapting to existence within cyberspace. The piece is hosted on Toronto-based Koffler Centre of the Arts’ website, and is part of “There are Times and Places”, a web-based exhibition (accessible at http://koffler.digital/times-and-places). Wuulhu, otherwise known as Bracken Hanuse-Corlett is a Wuikinuxv and Klahoose artist working from Vancouver, and is best known for his fusion of performance and digital media with traditional Northwest Coast forms and traditions.

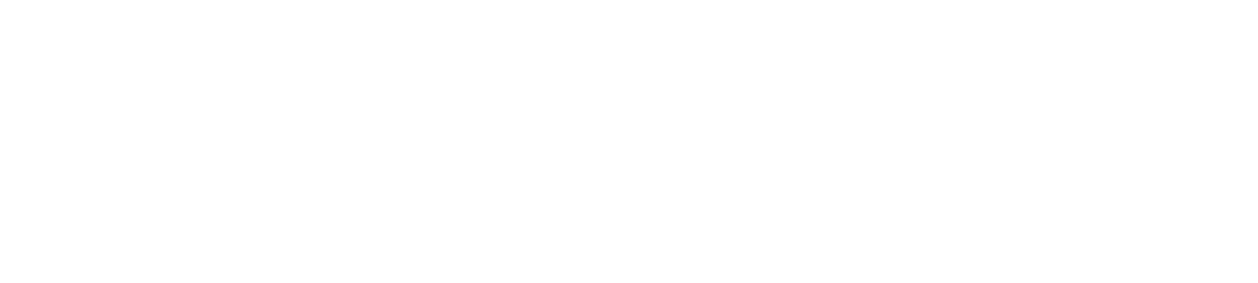

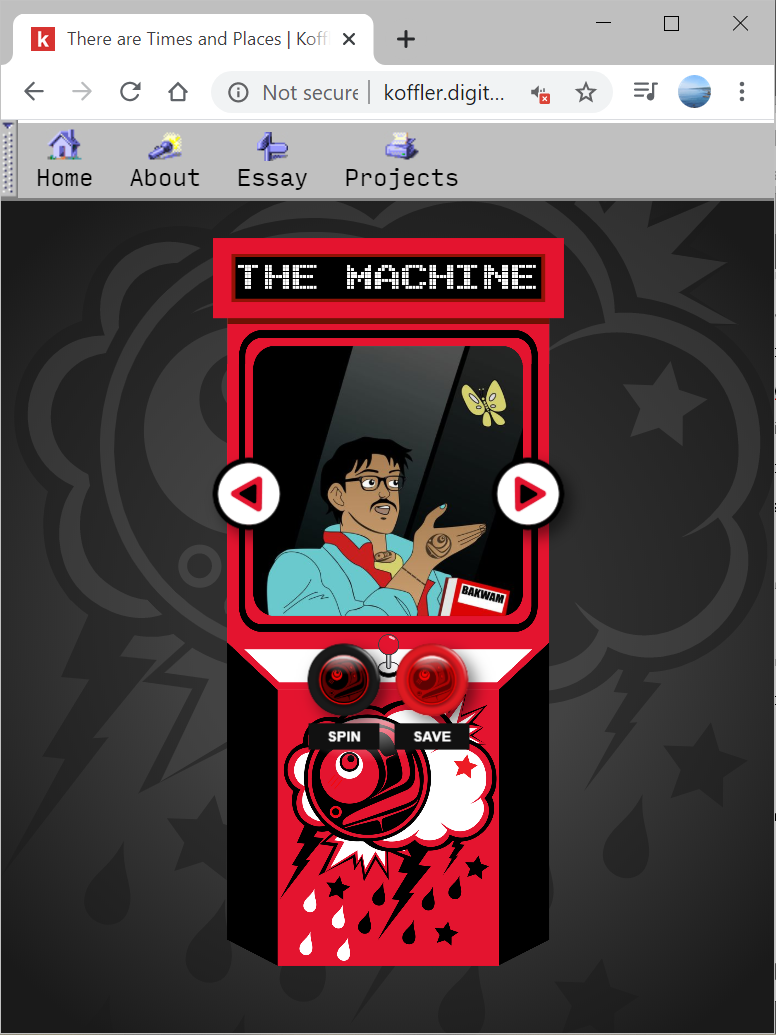

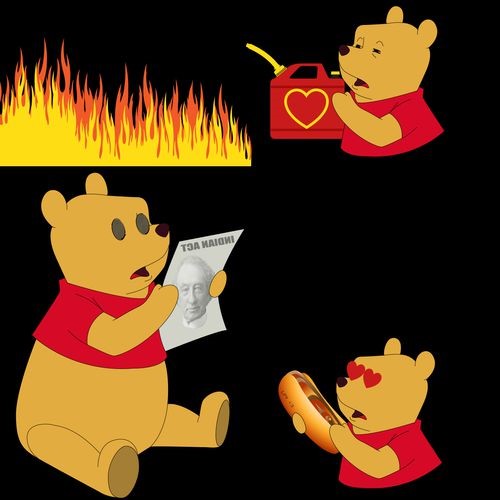

On entering the webpage which hosts the work, the viewer is presented with an arcade-style game machine labeled “THE MACHINE” appropriately, and decorated with an abstracted Northwest Coast design surrounded by cartoon-style lighting clouds and raindrops (Fig. 1). The square display screen of the machine displays a single meme designed by Wuulhu—a 1:1 ratio sharable image, mimicking memes which populate Social Media sites today. Clicking on the arrows to the left and right of the image allow the user to cycle through 40 images created by Wuulhu. These memes are created by riffing on popular formats and characters which are ubiquitous throughout internet culture, but are appropriated into Northwest Coast visual tradition by Wuulhu’s inclusion of formline designs and themes of Indigenous activism. Some of these memes hold a more concise narrative than others; in one, the popular “doge” photograph of a shiba inu is wrapped in a button blanket and adorned with a cedar hat, carrying a picket sign and megaphone (Fig. 2). In another, three Winnie the Poo characters appear in the same frame: one holding a can of oil to a line of fire, the next blindly staring at a piece of paper titled “Indian Act” with a picture of John A. Macdonald printed under it, and the third eating a formline-stylized hotdog with hearts instead of eyes (Fig 3). Furthermore, any indication of narrative is lost when the viewer clicks on the “SPIN” button, this feature combining three images randomly into an exquisite corpse style image the viewer is invited to save and share (Eg. Fig 4). The viewer can hit this button as many times as they want, creating an endless stream of memes which feature Indigenous-coded language about pipelines, water, and Oolichan grease.

Indigi-memes are a growing phenomenon among young Indigenous creators in Canada, and can be thought of within the theoretical framework laid out by Maskegon-Iskew, of challenging global capitalist structures. Emma Steen’s accompanying essay for the exhibition connects Meme Machine with Indigenous meme makers which inspired the piece, understanding Wuulhu’s work as an elevation of this social media phenomenon[14]. Following the legions of Indigenous meme-makers online, Wuulhu effectively appropriates internet-specific visual language that is global in scale, which in some ways represents the qualities of cyberspace which Todd calls attention to. Memes can be thought of as embodying this desire to “want everything, to go everywhere”, to proliferate throughout culture with a certain all-consuming hunger which Todd is so aware of. Indeed, a “whitinizing of cyberspace”; the invisibility of People of Colour online has been observed by scholars such as Kali Tal, with this phenomenon being tied to “a pedagogy of oppression that systematically submerges issues of race beneath a colourless version of liberal democracy” by Maskegon-Iskew[15]. Indigi-memes which Wuulhu draws from challenge these notions of dissolved identity on the internet, unapologetically bringing themes of colonization and genocide to light in the light-hearted form of internet memes[16]. Wuulhu uses very clear visual language to demarcate Indigeneity in his memes, from the use of formline design to the darkening of skin and hair on the meme-ified figures. The rhetoric of contemporary indigenous activism are present in ways which call back to Indigi-memes, with phrases such as “water is life” and “land back” dominating Meme Machine. Here, the challenge to global capitalism comes into play as young Indigenous creators assert their rights to land and water, their contestation of capitalistic exploitation of their land. These images can be seen as drawing a stake through an Internet which is some ways, has followed Todd’s vision of being a space which upholds hegemonies and dissolves individual bodies and identities. As written by Maskegon-Iskew, Wuulhu and indigenous meme makers are “transforming these networks and digital spaces”, “participating---from a position of self-determined, collaborative reflection on their unique world views---in the international definition of a new set of cultural practices: those evolving within digital art and creative electronic networking.[17]”

Returning to the possibilities held by the internet as an alternative to representation through traditional and colonially-rooted institutions such as museums, Meme Machine holds a complex spot in this narrative. As part of a Koffler Arts Centre exhibition, the piece was subsidized through corporate sponsors such as TD bank, and exists in a curatorial context that is not Indigenous. The Koffler Arts Centre strives to represent marginalized voices and further social change, but it still bears the burden of being supported by sponsors such as large banks and governmental institutions, like a vast majority of artist spaces in Canada. Artists like Wuulhu are caught in a space of contesting the powers at be through working with transcendent and limitless digital materials while simultaneously existing in contemporary economic climates and needing to sustain themselves as full-time artists. Here, Todd would ask if the internet can truly be a method of rupturing these power relations, or if it is “a clever guise for neocolonialism, where tyranny will find further domain”[18]. Indeed, as Steen pontificates, “the digital realm seems to function as a paradox, offering both a means of escapism for those seeking experiences outside of their physical realities as well as a place of surveillance and harmful philosophies”, a paradox which is apparent in the presentation of artists calling for justice and social change being funded by banks and governments which support the pipelines Wuulhu’s work contests[19]. However, although Meme Machine still exists within these constrictive power dynamics, it openly contests them. The work is liberated from the physical walls and ticketed admission of the museum, meaning there is no imperative to cater to a certain non-Indigenous, high-brow audience. The piece also goes beyond the Kollfler website through its integration of the viewer’s agency. The viewer can use the Meme Machine to recombine Wuulhu’s memes into their own, and export these newly made images to use them in any way they wish. The piece is not stagnant within the funding structure it exists in; through its digital medium it gains the ability to live beyond a singular encounter between artwork and viewer. It possesses the ability to extend out of it’s “exhibition space” and be live in the world of social-media image sharing, standing on the same platform as the Indigi-memes it draws from. Wuulhu’s piece can be thought of as a symbol of Indigeneity in cyberspace, existing within the confinements the internet exists in, and yet operating as a means to express Indigenous contestation without the representational restrictions of museum, with the ability to live beyond itself.

The internet as it stands today is not an idealistic utopia for un-inhibited art practices, freed from the tyrannies of colonial oppression. Nor is it static. Cyberspace is being continually renegotiated and reinvented by it’s inhabitants, with Indigenous artists enacting the networked quality Maskegon-Iskew wrote of to challenge the powers at be and disseminate their world-view on a global scale. The internet does posses the inherent ability to transcend certain physical structures of museums, of the concentration of ‘culture’ in urban centres and access to these spaces being restricted to a select demographic population. Meme Machine takes advantage of this and takes it one step further, allowing viewers to make the work their own and disseminate it through whichever way they see fit. As Todd observed in 1996, the internet is not inherently a place of nourishment but maybe it has the potential to become such a place. As Indigenous meme makers continue to assert their presence within the ‘whitenized’ and neo-colonial space of the internet, and as contemporary artists move towards digital medium in their practice, cyberspace becomes newly pliable. Indigenous artists are at the forefront of reworking cyberspace, of expanding it and appropriating it’s hegemonic qualities, to be a place where they can represent themselves, where they can enact their unique cultural values and contest the colonial and capitalistic forces which stand at odds with them.

[1] Michael M Ames, “How Anthropologists Stereotype Other People,” in Cannibal Tours and Glass Boxes: The Anthropology of Museums, (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1992), 54-58.

[2] Loretta Todd, “Aboriginal Narratives in Cyberspace,” in Immersed in technology: art and virtual environments ed. Mary Anne Moser and Douglas B. McLeod (MIT Press, 1996).

[3] Ahasiw Maskegon-Iskew, “Drumbeats to Drumbytes: Globalizing Networked Aboriginal Art” in Transference, Tradition, Technology: Native New Media Exploring Visual and Digital Culture, ed. Dana Claxton (Banff: Walter Phillips Gallery, Art Gallery of Hamilton and Indigenous Media Arts Group, 2005).

[4] Anna Laura Jones, "Exploding canons: the anthropology of museums," Annual Review of Anthropology 22, no. 1 (1993): 203.

[5] Ames, 50-54.

[6] Ames, 54.

[7] Quoted in Jones, 214-215.

[8] Jones, 215. Emphasis added.

[9] Todd, 179.

[10] Maskegon-Iskew, 192.

[11] Ibid, 201-202.

[12] Ibid, 206.

[13] Todd, 193.

[14] Emma Steen, “Time, Place and Cyberspace: who gets to play and how,” Times and Places, Koffler Centre for the Arts, 2019, https://content.koffler.digital/times-and-places/?/essay, para. 10.

[15] Kali Tal, “The Unbearable Whiteness of Being: African American Critical Theory and Cyberculture,” 1996, https://kalital.com/the-unbearable-whiteness-of-being-african-american-critical-theory-and-cybercultur/;

Maskegon-Iskew, 195.

[16] Lenard Monkman, “Indigenous meme creators point out harsh truths with dark humour,” CBC News, September 19, 2018, https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/indigenous-meme-creators-instagram-1.4828555.

[17] Maskegon-Iskew, 192.

[18] Todd 180.

[19] Steen, para. 2.

Ames, Michael M. “How Anthropologists Stereotype Other People.” in Cannibal Tours and Glass Boxes: The Anthropology of Museums, 49-58. Vancouver: UBC Press, 1992.

Jones, Anna Laura. "Exploding canons: the anthropology of museums." Annual Review of Anthropology 22, no. 1 (1993): 201-220.

Maskegon-Iskew, Ahasiw. “Drumbeats to Drumbytes: Globalizing Networked Aboriginal Art” in Transference, Tradition, Technology: Native New Media Exploring Visual and Digital Culture, edited by Dana Claxton, 189-218. Banff: Walter Phillips Gallery, Art Gallery of Hamilton and Indigenous Media Arts Group, 2005.

Monkman, Lenard. “Indigenous meme creators point out harsh truths with dark humour,” CBC News. September 19, 2018. https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/indigenous-meme-creators-instagram-1.4828555.

Steen, Emma. “Time, Place and Cyberspace: who gets to play and how.” Times and Places, Koffler Centre for the Arts, 2019, https://content.koffler.digital/times-and-places/?/essay.

Tal, Kali. “The Unbearable Whiteness of Being: African American Critical Theory and Cyberculture.” 1996. https://kalital.com/the-unbearable-whiteness-of-being-african-american-critical-theory-and-cybercultur/.

Todd, Loretta. “Aboriginal Narratives in Cyberspace” in Immersed in technology: art and virtual environments edited by Mary Anne Moser and Douglas B. McLeod, 179-194. MIT Press, 1996.